Degas’ bathers paintings – modern realist Aphrodites

Walk 2, map of lower Montmartre – Pigalle ; route and points of interest of the Montmartre walking tour Montmartre Artists’ Studios © OpenStreetMap contributors, the Open Database Licence (ODbL).

His focus shifts from opera ballerinas to nude female bathers

For the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition of 1886, Degas revealed that he would present a suite of nude women, “bathing, washing, drying and rubbing themselves dry, combing their hair or having their hair combed”.

The bather paintings he unveiled for the show and continued to produce right up to the end of his artistic career are among his greatest achievements.

Degas had a reputation for misogyny and liked a provocative statement; he is reported as saying that with the series he wanted to show women’s animal side. Yet soon after the exhibition he was producing works of grace with the emphasis on feminine sensuality.

For the models who made his work possible, Degas was hellish to work for. Surrounded by the clutter of props he assembled for the bathers series—tubs, jugs, towels, chairs, combs and changing screens—the sitters suffered. They were forced to remain motionless, with aching limbs, in awkward poses, swaying and silently cursing on the edge of balance.

Degas remained interested in the Paris Opera ballet dancers throughout his artistic career. His dancer paintings featured many figures and a wide range of actions.

With the bathers he now turned his attention to revisiting the most traditional of subjects in art: the nude.

Instead of a troupe of ballet dancers Degas zoomed in on just one figure, and concentrated his attention on catching individual moments of movement.

New city new art

Degas was a realist interested in the life happening around him in a changing and modernising Paris.

He was aware of his position as a bourgeois man near the top of the social hierarchy in the third French republic and he knew too that society was changing with a growing suburban working-class surrounding Paris.

The cityscape of Paris was being reinvented. Technology too made some startling advances: electricity replaced gas, photographs suddenly jumped into life as moving images, horses made way for motor vehicles and the entertainment industry took off as people had more money to spend.

With his horse racing pictures, his concerts and his café studies Degas recorded the modern phenomenon of leisure.

With his ballet series, where Degas obsesses on painting movement, was he reflecting on the accelerating changes he saw in society?

With his bathers—where we see bodies in postures of instinctive balance—was he perhaps musing on the delicate equilibrium of competing social forces in the modern city?

For his female bathers series Degas was never going to paint an academic salon scene of nude nymphs and goddesses gambling in an imagined mythological landscape. That was where the nude was traditionally situated in French art, out of space and time. In that imagined landscape elevated principles of ancient culture were the camouflage for some good old-fashioned male titillation.

No. If he was to paint nudes they had to be modern, they had to be of his time and place, and they had to be stripped of the soft-focus frisson of the salon tradition.

In the Paris of Degas’ time standards of hygiene were improving as buildings got better access to running water. It was in the privacy of her own bathroom that Degas situated his contemporary female nudes.

Location: 21 Rue Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, 1882 – 1890

By 1886 we find that Degas had moved again but never too far from the Pigalle or lower Montmartre area. His new address was 21 Rue Jean-Baptiste Pigalle and he was here from 1882 – 1890.

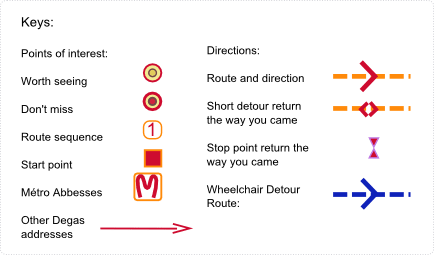

This address does not feature on the circuit but it is easy to make a short detour and see. Instead of following the map and turning right after point 12 cross over Rue Pierre Fontaine and carry on straight down the street to number 21 Rue Jean-Baptiste Pigalle. The direction is indicated in yellow in the detour map above.

Don’t forget to turn around and come back on track with the walk though.

The Louvre Crouching Aphrodite

The idea of a single figure bathing may have been seeded in Degas’ mind when he visited the Louvre and would have surely viewed, and probably sketched, the ancient Crouching Aphrodite sculpture.

Degas would have also seen Aphrodite figures on his extensive travels in Italy, and was well aware of the classical tradition.

The statue in the Louvre is a Roman-era copy of an earlier Hellenistic Greek sculpture called The Aphrodite of Knidos. The original was very famous because for the first time in ancient art it showed a nude female figure—the supremely beautiful and desirable goddess of love, Aphrodite herself.

The Aphrodite of Knidos stood in a specially constructed round building so that its many male admirers could stroll round, examine, discuss and leer at her physique from all angles.

Aphrodite is crouching whilst bathing

The fine Louvre example shows Aphrodite, crouching to bathe. The pose allowed the sculptor to detail the voluptuous, fleshy folds of the goddess’ torso. The smooth milk-white marble models perfectly her generous and sensual curves. Her position is unusual but she remains graceful and poised.

The intended eroticism of the original piece came from the fact that Aphrodite was shown surprised by someone whilst bathing. She reaches for a towel and makes some attempt to cover herself.

Because we only see Aphrodite but her gaze and pose signal her awareness of some other presence, the viewer is placed in the role of voyeur, spying on the sublime goddess of beauty.

Degas’ modern realist Aphrodites

Degas knew about the ogle-value of nude female figures in the history of art. He would probably have seen works by Titian, for example his beguiling Venus of Urbino on his travels in Italy.

Female nudes came with sensuality and a touch of voyeurism built-in. That is why Degas played with expectations when he revealed his artistic perspective for his bathers: it was as though they were viewed “through a keyhole” as he is reported as saying.

As usual he was being ironic and provocative, playing with the innuendo of voyeurism whilst at the same time drawing attention to the naturalism of the poses.

In fact when we as viewers look at a Degas bather we just observe what happens when someone, female, bathes.

The women he portrayed were behaving as though they were alone, going about their bathroom routine; washing, drying themselves or combing their hair.

In the Degas bather paintings there is no implied presence of a secondary actor or intrusive spectator. There is no implied interaction—as with the ancient Aphrodite sculptures—with the viewer as voyeur. The bathers are pragmatic notes of female attitude and balance and, unlike the Aphrodite or old master examples, are not designed to elicit an erotic response.

Getting yourself washed, in Degas’ time took place either in a bathroom or bedroom. Because these are intimate domestic scenes with the focus on just one actor, there is less depth of field and less distraction than in, for example, the ballerina series. The backgrounds in most of the series is generalised: a chair, a towel, wallpaper, perhaps some curtains or a screen for dressing.

Carefully prepared studies of spontaneous gestures

The pictures look natural but there was nothing spontaneous about the way he had prepared the nude bather series.

Degas was never looking through a keyhole, getting only a partial view. He had set everything up in his studio so he could get a full view from any angle or height he chose.

He brought all the props — tubs, baths and armchairs — to his studio, so we can imagine the dull, tinny sound of the tubs bouncing off the walls and scraping the plaster as the complaining delivery men struggled to get them up the stairs at 21 Rue Jean Baptiste Pigalle.

The most famous image of the bathers series shown at the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition of 1886 is The Tub in The Orsay Museum in Paris.

The Tub

The pose of the woman squatting, ball-like, in a tub or shallow zinc basin recalls the Louvre Crouching Aphrodite.

The figure is sponging the back of her neck and is seen from above. We only see her back, flank and hair, her face is hidden. The elegant rounded jugs on the table close to the model reference her fluid lines.

Her body has a sculptural solidity suggested by areas of shadow and subtle pastel highlights. Degas is concentrating on physique, posture and gesture and ignores the character or psychology of his subject.

The illusion of solidity was helped no doubt by the figurines Degas made and used to help him translate sculptural bearing into painting—see the Little Dancer page.

Unlike the Louvre Aphrodite, this bather is entirely unaware of a viewer and so there is no posing or reaction to a spectator.

The tub is grey and uninviting, it looks as though there is only a very small amount of water for her to use, hardly enough to even cover her fingers or toes. Bathing in a cold room in winter would have been unpleasant.

Blue patches of pastel on the floor suggest that some of the precious water has splashed out.

The pose is harmonious but awkward, we can easily imagine the figure getting cramp.

The bather is not a reclining classical nude or a goddess from Greek mythology, this is a modest modern woman in a tub attending to her hygiene painted in the realist manner. Scenes exactly like this were happening all over 1880s Paris as Degas set about his bathers series. This is Degas’ take.

Woman Bathing in a Shallow Tub

A second picture premiered at the 1886 Impressionist show, Woman Bathing in a Shallow Tub amplifies the realism by featuring the bather’s bumpy, bony pelvic region. The woman braces herself between left knee and elbow as she stoops down to sponge her foot.

The hard task of bathing, with the attendant risks of slipping or losing balance, is offset by the large welcoming open towel draped over the arms of the chair which is about to envelope the bather.

The bathers’ highly original poses

Two more examples of works from the same show are Woman Drying Her Left Foot and Woman Drying Her Foot.

The first portrays an unusual egg-like posture as the woman folds over on herself to reach her foot; the second an acrobatic diagonal composition as the model dries her foot placed on the lip of the bath.

The dynamic poses highlight the adaptability and plasticity of the female physique transforming itself into unexpected and unconventional combinations.

As with his earlier Little Dancer statue, was the starchy bourgeois Degas quietly appreciating the suppleness of his female model’s limbs?

Degas’ studios, apartments and major works in the Pigalle area of Montmartre

A cool reception for Degas at the eighth Impressionist exhibition of 1886

Degas took a realistic look at modern women bathing in 1886. Many critics, however, did not like Degas’ version of reality and attacked the works for their unusual viewpoints and obscure poses. The images were considered unsettling, ugly and artificially contorted.

Showing real, contemporary, naked women in modern domestic situations in tubs was still too radical for many of them.

Degas stoked the critics further and helped to reinforce his reputation for misogyny by remarking that he was portraying women’s “animal” side.

Degas drops out of the exhibition circuit

Degas had always been an excellent draughtsman and chose his subject matter and style without compromise. He stuck to his guns and, with time, his style was recognised by dealer and collector alike.

Following the backlash, he decided to no longer expose himself to the critical ridicule and popular humiliation that his presence at large public events attracted.

Degas took no further part in set-piece exhibitions after the last Impressionist show in 1886. He only accepted invitations to some low-key dedicated events with his dealers.

Because he no longer took part in high-profile shows, Degas’ seems to have unclamped a bit. Without dropping realism he now featured much more sensuality in his nude bather works.

Degas’ bathers paintings and feminine sensuality

The Woman Having Her Hair Combed

The Woman Having Her Hair Combed is clearly different in content and style from, for example, the tub portraits.

The bather has escaped the inconvenience of squatting and twisting to get washed in some tepid water in a shallow, slippery, tin tub. She has gone upmarket and moved into a warm comfortable bourgeois environment.

She is sitting on an oversized, thick towel which is spread on a mustard-coloured, luxury upholstered bench. Unusually—because with Degas’ bathers the viewpoint is normally from the back with the face hidden—we see a three-quarter nude view and the model’s face. She is looking up and having her long red hair combed by a maid whose head has been cropped.

Unlike the jutting bones of some of the working class tub models, here the subject has milky, silky skin and an elegant well formed flowing physique.

The bather is easy on the eye and Degas has added a sensual touch: as her head is being tugged back by the maid’s efforts to comb her long hair, she braces herself, hand on hip and knees locked together. Her resistance to the tug of the maid combing her hair is shown by her left hand digging into her soft fleshy side.

The Woman Combing Her Hair

Staying in the Metropolitan Museum, The Woman Combing Her Hair painted between 1888-90 is executed with fizzing pastel strokes.

The well-proportioned, substantial, elegant woman sits cross-legged on a heavy towel with a fine comfortable chair in the background. We have returned to the back view, with the face hidden.

Degas has found a particularly fine line between the combing arm, back and hips, as the woman attends to her beautiful and abundant auburn hair.

Degas indicates contour and sheen with delicate pastel greens and purples.

Degas moved, in 1890, to his next address 23 Rue Ballu, which is close to point 7.

Location: 23 Rue Ballu, 1890 – 1897

Rue Ballu is not far from point 7. You can easily access it by dropping downhill on Rue Blanche. Here in yellow is the detour map to Rue Ballu.

Navigating from point 7, you would walk down the slope on Rue Blanche and take the third street on your right which is Rue Ballu.

In 1897 Degas moved again, this time to 37 Rue Victor Massé which is point 13 on the map.

Location: 37 Rue Victor Massé, 1897 – 1912, point 13

The building Degas lived in was demolished in 1912, the apartment block we see now was put up in the same spot post 1912.

If we turn around from where Degas’ front door would have been we can see some 1960s flats. These replace the famous Bal Tabarin which was a dancehall and popular entertainment venue and was situated right opposite Degas’ apartment block.

The Bal Tabarin featured an ornate Art Nouveau carnivalesque façade from the first decade of the 20th century. It too was demolished — in 1966 — as the Paris city authorities once again forgot about traditional grass roots Montmartre culture. It made way for the standard format residential apartments we now see in its place.

After the Bath: Naked Woman Rubbing her Neck

After the Bath: Naked Woman Rubbing her Neck is another wonderful image of femininity. It dates from the time of Degas’ arrival at point 13. The picture is in the Orsay Museum, Paris.

Once again the model’s face is hidden, we cannot judge her character or mood; what we have in the picture is a beautiful but anonymous sculptural female ‘specimen’.

She is sitting on the edge of a bath, the clean, cool, hard metallic lines contrast with the full, fleshy roundness of her hips and buttocks.

Light floods in and illuminates her flank. Her position, on the lip of the bath, pushes her lower half towards the viewer and amplifies the graceful curve of her back. The shadow cast on her back too helps define the sinuous line between shoulder and hip.

Her form is contrasted with some strong vertical background panels. The shapes represent, perhaps, a dressing screen, a curtain, and wallpaper but, as in many later Degas works, are alluded to by colour rather than form.

Degas appears to be slipping away from his traditional framework of strict realistic representation and shifting to cues given by colour of what may be behind the model. That pleasant background wash of colour means our primary focus is now on the presence of the bather and her elegant attitude.

In this work it’s obvious that Degas is revelling in the female form, he is unreservedly paying homage to female beauty and sensuality. There is no trace of misogyny here.

After the Bath: Naked Woman Rubbing her Neck is a sensual even erotic image and because of that was no doubt more commercially viable than some of the earlier more true-to-life tub bathers.

Concession is made to the audience’s gaze but in an unconscious and natural way. The woman is very pleasing on the eye and her pose does show off her fine physique and beauty. Still the impression is that this is the pose she adopts routinely to rub her neck.

We are not intruding on her private space or playing the voyeur because there is no interaction between us and her. It is simply a neutrally observed and realistic image of an anonymous, beautiful, young woman drying the back of her neck.

The bathers’ unconscious equilibrium

Most people are hardly aware of equilibrium and only become fully conscious of it when it disappears and we fall. Balance, for many, is unconscious, it is part of daily reality, keeping us on an even-footing.

Degas with his art wanted to capture that instinctive sense and, even in the most banal situation—like drying yourself whilst perched on the edge of a bath—help show us its momentary presence.

Woman at Her Toilette

The Woman at Her Toilette is a late work from sometime between 1900 – 05 and would have been painted in the apartment that used to stand here, point 13, 37 Rue Victor Massé.

Degas’ vision had been slowly deteriorating for many years and he was becoming reclusive. Already in 1893 he said “I work with the greatest difficulty and yet I have no other joy”.

In The Woman at her Toilette we see Degas returning to one of his favourite poses: a woman holding her hair and vigorously rubbing dry the back of her neck. As usual the view is of her back and flank. She has pitched into her drying routine with such energy that her torso is flexing to the left.

The vigorous rubbing seems to have animated the background which, like the primitive films of the time, flickers into life. A curtain billows forward to hide her lower half, wallpaper turns to multicoloured thread and dances off the wall, the staple of the Degas bather series, the upholstered chair, is suggested by a swirl of yellow, a towel is a shaft of brilliant white, whilst the blue light from the window seems to be tumbling onto her back like a waterfall.

The old misogynist who admired women

The nude female bathers are among his greatest achievements and could not have been executed by a true misogynist. If he was as misogynistic as he is portrayed, why did he continually paint girls and women?

Most of Degas’ artistic life revolved around girls or women. Great art doesn’t come from distaste or crippling prejudice, it translates a passion and the artist has to be willing to travel in the direction of the idea as it forms and takes life of its own. That progression can’t take place if he is bogged in a fixed and limiting position.

Degas could never have achieved what he did if he had nothing but contempt for women. From years of closely observing women and girls he probably knew that they possessed a common force greater than any of his personal prejudices. He stuck with the prejudice, it was what people expected of him and part of his identity; yet if we look frankly at the female bathers the art tells another story.

Degas’ reputation as an artist is secure: he was a brilliant artist. It is now time to blow away the women-hating smokescreen that he created for himself so he could keep people at bay and work in peace.

The bathers series tell us much more than the accepted stereotype of the stuffy and difficult Degas. These wonderful paintings show us a fine observer of femininity who had a quiet admiration for feminine resilience, adaptability and dignity.

Degas’ last move

Degas had to move out of point 13 in 1912 when the building he lived in was demolished. He was forced to move his entire collection to 6 Boulevard de Clichy, where he died in 1917. The move seems to have broken his desire to work. As far as is known Degas was not artistically active during this final period.

This ultimate address is not on the walk as there is little to see except a plaque on the wall outside. I have indicated the direction on the map with red arrows beyond point 2.

All photographs © David Macmillan except: (1), (2), (3), (4).

(1) Edgar Degas artist QS:P170,Q46373, Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 031, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

(2) Unknown, Bal Tabarin 1904, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

(3)Edgar Degas artist QS:P170,Q46373, Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 045, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

(4) Edgar Degas author QS:P170,Q46373, Edgar Degas self portrait photograph, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons